+–

Agammaglobulinemia: X-Linked and Autosomal Recessive

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) and Autosomal Recessive Agammaglobulinemia (ARA) are types of PI resulting from the failure of B-lymphocyte precursors to mature into B-lymphocytes and ultimately plasma cells. Without the cells responsible for producing antibodies, XLA and ARA patients have severe deficiencies of all types of immunoglobulins. They are prone to developing infections that occur at or near the surfaces of mucus membranes, such as the middle ear (otitis), sinuses (sinusitis) and lungs (pneumonia or bronchitis). Infections of the skin and gastrointestinal infections can also be a problem, especially those caused by the parasite Giardia.

The defect in the B-cells is present at birth and infections may begin at any age. On physical examination, most patients with XLA or ARA have very small tonsils and lymph nodes. Patients with either XLA or ARA should not receive any live viral vaccines, such as live polio, the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, the chicken pox vaccine (Varivax) or the rotavirus vaccine (Rota-teq). Most patients with XLA or ARA who receive immunoglobuline treatment on a regular basis will be able to lead relatively normal lives. A full and active lifestyle is to be encouraged and expected.

+–

Ataxia Telangiectasia

Ataxia Telangiectasia (A-T) is an inherited disease that affects several body systems, including the immune system. Normally diagnosed in childhood, patients with A-T may have an unsteady, wobbly gait (ataxia) that gets worse as they get older, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or speaking (dysarthia), dilated, corkscrew-shaped blood vessels (telangiectasia) on the whites of the eyes and on sun-exposed areas of skin, immunodeficiency involving both humoral (B-lymphocytes) and cellular (T-lymphocytes) immunity; and a high rate of cancer. Not all the features of the syndrome are present in all people with A-T, and the severity of each symptom varies a great deal from person to person. Those persons with a severe humoral immunodeficiency preventing them from making antibodies, will likely require immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Patients with A-T have an increased susceptibility to infections, especially those of the lungs and/or sinuses. They are also at an increased risk for developing all types of cancers, but especially those of the immune system (lymphomas or leukemias). Cancer occurs in about 25% of all patients with A-T. Children with A-T should be able to attend school, but will likely eventually require full-time aides to assist with the activities of daily living while at school, and often require the use of a wheelchair for at least part of the day by the age of 10-12 years. Because A-T involves neurological deterioration, by the teenage years most patients will require a wheel chair and other adaptive devices, and as of this time, most have a reduced life expectancy.

+–

Chronic Granulomatous Disease and Other Phagocytic Cell Disorders

Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) is a genetic disease in which the body’s cells called phagocytes, which destroy various invaders, do not make hydrogen peroxide and other chemicals needed to kill certain bacterias and molds. As a result, patients with CGD can defend against most infections, but not those related to specific bacteria and fungi. They also get too many immune cells forming “knots” called granulomas. CGD patients may also suffer from excessive inflammation even when there is no infection present, which can cause diarrhea, as well as bladder and kidney problems.

Infections in CGD may involve any organ or tissue, but the skin, lungs, lymph nodes, liver and bones are the usual sites. Infections may rupture and drain with delayed healing and residual scarring. Pneumonia is a common problem, as are bowel problems. About 40-50% of patients with CGD develop inflammation of the intestine, often incorrectly diagnosed as Crohn’s disease. Early diagnosis and prompt, aggressive use of appropriate antibiotics, is the best way to fight CGD infections. Preventive treatment with antibiotics and antifungals is recommended. People with CDG should avoid contract with brakish water, the handling of garden mulch in routine gardening tasks, as well as activity in dusty conditions, such as cleaning garages or cellars. Patients with CGD can expect to live well into adulthood and enjoy productive lives.

Other Phagocytic Cell Disorders involve a specific kind of white blood cell, called the polymorphonuclear granulocyte (PMN), also known as a neutrophil. Low numbers of these granulocytes, or their inability to kill organisms, similar to that in patients with CGD, lead to disorders called neutropenias, of which there are several types. Neutropenias can occur at birth and can be life-long. Depending on its severity and duration, neutropenia can lead to serious and fatal infection or intermittent infection of the skin, mucus membranes, bones, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, or blood stream (sepsis).

+–

Common Variable Immune Deficiency

Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID), characterized by low levels of serum immunoglobulins and antibodies, causing increased susceptibility to infection, is one of the most frequently diagnosed primary immunodeficiencies, especially in adults. While it is thought to be due to genetic defects, the exact cause of the disorder is unknown in the large majority of cases. The degree and type of deficiency of immunoglobulins, as well as the course of the disease, varies from patient to patient. In the majority of cases, diagnosis is not made until the age of 30 or 40.

CVID should be suspected in children or adults who have a history of recurrent bacterial infections involving ears, sinuses, bronchi and lungs. It may also cause other diseases including arthritis in knees, ankles, elbows and wrists, or endocrine disorders, such as thyroid disease. Gastrointestinal complaints such as abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and weight loss are not uncommon in CVID. Finally, patients with CVID may have an increased risk of cancer, especially cancer of the lymphoid system or gastrointestinal tract. Treatment of CVID centers on immunoglobulin replacement therapy combined with antibiotic therapy, which, in the absence of significant T-lymphocyte defect or organ damage, almost always brings improvement of symptoms and enhanced quality of life.

+–

Complement Deficiencies

Complement Deficiencies affect individual components of complement, the term used to describe a group of more than 30 serum proteins that are critically important in the defense against infection. These complement proteins are not activated until triggered by an encounter with a bacterial cell, a virus, an immune complex, damaged tissue or other substance not usually present in the body. Their activation is a cascading event like the falling of a row of dominoes, following a specific order to achieve the end result of protection from infection. There are three activation pathways, based on the types of substances and proteins that initiate the activation.

Patients with Complement Deficiencies encounter a variety of clinical problems that depend on the role of the specific complement protein in normal function. Symptoms of possible complement deficiencies include recurrent mild or serious bacterial infections, autoimmune disease, or episodes of angiodema (a painless or often dramatic swelling under the skin, or a swelling in the intestines, which can be extremely painful). Very rarely angiodema in the brain can be fatal. This swelling does not respond to antihistamines or epinephrine. The list of complement-related problems includes renal disease, vasculitis (blood vessel inflammation) and age-related macular degeneration. The various types of treatment therapies are targeted to specific deficiencies in the three different activation pathway components. These treatments are in their infancy at this time, but more should become available in the near future.

+–

DiGeorge Syndrome

DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS) is caused by abnormal migration and development of certain cells and tissues during fetal development. During this development, the thymus gland may be affected and T-lymphocyte production may be impaired, resulting in low T-lymphocyte numbers and frequent infections. While the genetic defect is the same in the majority of DGS patients, its manifestations vary. Patients with DGS may have any or all of the following: unusual facial appearance, heart defects, thymus gland abnormalities, autoimmunity, parathyroid gland abnormalities, or other developmental abnormalities including cleft palate, poor function of the palate, delayed acquisition of speech, and difficulty in feeding and swallowing. In addition, some patients have learning disabilities, behavioral problems, psychiatric disorders and hyperactivity.

Therapy for DGS is aimed at correcting the defects in the affected organs or tissues. Therefore it depends on the nature of the different defects and their severity, as does the outlook for people with DGS. The severity of heart disease is usually the most important determining factor. Therapies may include calcium or hormone supplementation, medications, corrective surgery, or immunoglobulin replacement.

+–

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a severe systemic inflammatory syndrome that can be fatal. Not always inherited, it can sometimes occur in people with medical problems that can cause a strong activation of the immune system, such as infection or cancer. In these settings it is called Secondary HLH. Primary HLH, also called Familial HLH, is caused by specific, inherited genetic defects. HLH occurs when histiocytes and lymphocytes, cells critical for fighting infection, become overactive and attack the body rather than just bacteria and viruses. These cells attack blood cells and bone marrow in particular, as well as the spleen, liver, lymph nodes, skin, and even the brain. Symptoms may include a high and unremitting fever, rash, hepatitis, jaundice, an enlarged liver and spleen, low counts of all blood types, and enlarged lymph nodes. Confusion, seizures, and even coma may also occur.

Primary HLH is a rare disease, reported in about 1 per 50,000 births worldwide each year. The genetic mutations are present at birth and patients often become ill in the first few years of life. If not detected and treated, Primary HLH is usually fatal, typically within a few months. Even with treatment the prognosis is sometimes only a few years, unless a bone marrow transplant can be successfully performed. If Secondary HLH is detected promptly and treat aggressively, the prognosis may be better. Treatment may include aggressive courses of immunosuppressants and anti-inflammatory agents, chemotherapy, antibiotics, antiviral drugs and IVIG. These can diminish or slow the effects of the disease, but relapse is to be expected in patients with Primary HLH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant is the only therapy with the possibility of permanently restoring normal immune function.

+–

Hyper IgE Syndrome

Hyper IgE Syndrome (HIES) is a rare PI disease characterized by eczema, recurrent staphylococcal skin abcesses, recurrent lung infections, a high number of eosinophils, a type of disease-fighting white blood cell, in the blood (eosinophilia), and high serum levels of IgE (Immunoglobulin E), an antibody that causes allergic reactions. Patients with HIES are susceptible to food allergy, hemolytic anemia, vasculitis (inflammation within blood vessels), encephalitis (brain inflammation) and vascular brain lesions. They are also at increased risk for cancers, particularly lymphomas. There are two forms of the disease: AD, autosomal dominant and AR, autosomal recessive. While they share overlapping features, they have distinct clinical manifestations, courses, and outcomes.

Therapy for HIES remains largely supportive. Preventive antibiotic therapy is used against recurrent respiratory infections. Skin care and prompt treatment of skin infections is important. Antifungals are used to treat candida infections (candidiasis). Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is used with poor antibody responses to vaccination. Patients with HIES require constant vigilance with regard to infections and development of chronic lung disease. With early diagnosis and treatment of infections, most AD-HIES patients do fairly well. The more severe nature of AR-HIES should prompt early consideration of bone marrow transplantation, which is curative.

+–

Hyper IgM Syndrome

Hyper IgM Syndrome (HIGM) is characterized by decreased levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the blood and normal or elevated levels of immunoglobulin M (IgM). These different types of antibodies perform different functions but are important in fighting infections. A number of different genetic defects can cause HIGM syndrome, so there are several variants of the disease. The most common form is inherited as an X-chromosome-linked defect. Patients with HIGM are susceptible to recurrent and severe infections. In some cases they are at increased risk for opportunistic infections and cancer as well.

Most patients with HIGM syndrome develop symptoms in the first or second year of life, typically with increased susceptibility to recurrent upper and lower respiratory infections. Most infections are caused by bacteria, but viral illnesses are also frequent and severe. Since all forms of HIGM syndrome have a severe IgG deficiency, they require immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Those with antibody class switching defects treated with immunoglobulin replacement therapy can live long and productive lives. Those with defects in T-cell activation characteristically have more significant immune deficits and may encounter additional problems such as susceptibility to more dangerous types of infections, autoimmune disorders and cancer as further challenges. Hematopoietic stem call transplantation is encouraging for those with the more severe disease.

+–

IgG Subclass Deficiency

The main immunoglobulin (Ig) in human blood is IgG. This is the second most abundant circulating protein and contains long-term protective antibodies against many infectious agents. IgG is a combination of four slightly different types of IgG, called IgG subclasses: IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4. When one or more of these subclasses is persistently low and total IgG is normal, a subclass deficiency is present. Although this deficiency may occasionally explain a patient’s problems with infections, IgG Subclass Deficiency is a controversial diagnosis and experts disagree about the importance of this finding as a cause of repeated infections.

Patients with any form of IgG Subclass Deficiency occasionally suffer from recurrent respiratory infections. These may be ear and/or sinus infections, as well as bronchitis and pneumonia. The mainstay of treatment includes use of antibiotics to treat and prevent infections. Additional immunization with pneumococcal vaccines may be used to enhance immunity. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is an option for selected symptomatic patients with persistent IgG subclass deficiencies, documented poor responses to vaccines, and who fail preventive antibiotic therapy. The outlook for patients is generally good. Many children appear to outgrow their deficiency as they get older, making frequent re-evaluation of IgG Subclass Deficiencies important.

+–

Innate Immune Defects

Innate Immune Defects are PI diseases resulting from defects in the innate immune system, a system of calls and mechanisms that defend the host from infection in a non-specific manner, requiring no specific “training” to do their jobs. These innate immune defects include those in Toll-like receptor (TLR) cells (targeting microbial infection), natural killer (NK) cells (targeting viral infections or malignant cells) and interferon-g/interleukin 12 (IFN-g/IL-12) simulation in cells (targeting mycobacterial infection causing tuberculosis and related infections as well as salmonella infections). Depending on the type of defect, patients with innate immune defects may be more susceptible to allergy, asthma, atherosclerosis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Herpes simplex virus (causes cold sores and genital herpes), Epstein-Barr virus (causes infectious mononucleosis, varicella virus (causes chicken pox and shingles), tuberculosis and salmonella.

The usual treatment for these defects is antibiotic therapy to treat acute infection. Preventive antibiotic therapy is also used. Some health care providers have prescribed immunoglobulin replacement therapy to prevent infection. Patients with defects of the innate immune system are being recognized with increasing frequency. Since these illnesses are rare and only recently identified, the long-term outlook has not yet been established.

+–

NEMO Deficiency Syndrome

NEMO (NF-kappa B Essential Modulator) Deficiency Syndrome is a complex disease caused by genetic mutations in the X-linked NEMO gene (also known as IKK gamma or IKKG). It can involve many different parts of the body and often manifests in different ways in different individuals. The most common symptoms are skin disease and susceptibility to certain bacterial, pus-inducing infections that can be severe and affect virtually any part of the body – lungs, skin, central nervous system, liver, abdomen, urinary tract, bones, and gastrointestinal tract. Almost all cases of NEMO appear in boys.

Therapy for the NEMO syndrome is aimed at preventing infections and complications stemming from infection. Patients receive immunoglobulin replacement for the antibody immunodeficiency. They also receive preventive antibiotics, especially against Pneumococcus, Staph, and mycobacterial infections. The relatively recent recognition of the disease, its rarity, and its range of severity give little clear guidance with regard to long-term outcomes.

+–

Selective IgA Deficiency

Selective IgA Deficiency is a PI characterized by an undetectable level of immunogobulin A (IgA) in the blood and secretions but no other immunoglobulin deficiencies. While IgA is present in the blood, most of it in the body is in the secretions of mucosal surfaces including tears, saliva, colostrum, genital, respiratory and gastrointestinal secretions. The IgA antibodies play a major role in protecting us from infections in these areas. Relatively common in Caucasians (1 in 500 people), many affected people have no illness as a result. Others may develop significant clinical problems – recurrent ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, allergies, gastrointestinal infections and chronic diarrhea. They may also experience autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and immune thrombocytopenic purpura as well as those affecting the endocrine or gastrointestinal systems.

Treatment of the complications associated with Selective IgA Deficiency should be directed toward the particular presenting problem. Patients with chronic or recurrent infections, for example, need appropriate antibiotics, ideally organism-specific, rather than broad-spectrum. Autoimmune diseases may be treated with anti-inflammatory drugs. Treatment of allergies follows general allergy treatment. Although Selective IgA Deficiency is usually one of the milder forms of PI, it may result in severe disease in some people. Therefore, it is difficult to predict the long-term outcome for individual patients.

+–

Selective IgM Deficiency

Selective IgM Deficiency is a rare immune disorder in which a person has no or low immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies, with normal levels of other antibodies. IgM is the first antibody the system makes to fight a new infection. Therefore, when a person does not have enough IgM the body may have difficulty fighting infections. The disorder may occur as a primary disorder (on its own) or more commonly, as a secondary disorder (associated with another underlying disease or condition). It may occur in association with some cancers, autoimmune diseases, allergic diseases and gastrointestinal diseases. Symptoms may include repeated viral, bacterial, or fungal infections, such as ear infections, bronchitis, sinusitis, and pneumonia.

The cause of Selective IgM Deficiency is not known. Measures should be taken to prevent infections and /or to treat them as soon as possible. Treatment for Selective IgM Deficiency may include vaccination, aggressive allergy treatment, preventive antibiotics and immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

+–

Severe Combined Immune Deficiency and Combined Immune Deficiency

Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID, pronounced “skid”) is a potentially fatal immunodeficiency in which there is a combined absence of T-lymphocyte and B-lymphocite function. There are at least 13 different genetic defects that can cause SCID. Generally considered to be the most serious of the PI diseases, it can lead to extreme susceptibility to very serious infections. Fortunately, effective treatments, such as stem cell transplantation, exist that can cure the disorder. Early identification of SCID, including newborn screening, can make life-saving intervention possible before infections occur. Bone marrow transplants given in the first three months of life have a 98% success rate. Gene therapy is also promising for several more types of SCID.

Severe infection is the most common presenting symptom of patients with SCID, including pneumonia, meningitis, bloodstream infections, chicken pox, polio virus, and measles virus, among many others. Fungal infections as well as persistent diarrhea, resulting in growth failure, are also a common problem in children with SCID. Since vaccines for chicken pox, measles, mumps, rubella and rotavirus are live virus vaccines, children with SCID can contract these viruses if they receive those immunizations. These should not be given to new babies until it has been determined that the infant does not have SCID. Immunoglobulin therapy should be given to all infants with SCID. In addition, until definitive treatment such as stem cell transplantation, the infant with SCID must be isolated from children outside the family, especially from young children, to avoid the possibility of bringing infectious illness into the home. Without a successful stem cell transplant, enzyme replacement therapy or gene therapy, the patient is at constant risk for severe or fatal infections.

+–

Specific Antibody Deficiency

Among the five classes of immunoglobulins, immunoglobulin G (IgG) has the predominant role in protection against infection. Some patients have normal levels of immunoglobulins and all forms of IgG, but do not produce sufficient specific IgG antibodies to protect against the types of organisms that cause upper and lower respiratory infections. These patients are diagnosed with Specific Antibody Deficiency (SAD). Recurrent ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis and pneumonia are the most frequently observed illnesses in patients with SAD. It occurs most commonly in children, although they may “outgrow” it over time. Adults with similar symptoms and poor response to vaccination are less likely to improve over time.

Treatment may include antibiotics as well as immunoglobulin replacement therapy. The outlook for patients with SAD is generally good. Many children appear to outgrow their deficiency as they get older, usually by age 6. For those for whom the deficiency persists treatment may prevent serious infections and the development of impaired lung function, hearing loss, or injury to other organs.

+–

Transient Hypogammaglobulinemia of Infancy

An unborn baby makes no Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody and only slowly starts producing it after birth. However, starting at about the 6th month of pregnancy, the fetus begins to receive maternal IgG antibody through the placenta. This increases during the last trimester of pregnancy until at term birth the baby has a level of IgG equivalent to that of the mother. The baby continues to get additional antibody via breastfeeding, eventually producing its own supply. Between 3 and 6 months all infants have low levels of IgG as a result of the maternal IgG falling and the infant’s IgG just starting to be made. Transient Hypogammaglobulinemia of Infancy (THI) is defined in infants over 6 months of age whose IgG is significantly lower than 97% of infants of the same age. This is most commonly corrected by 24 months of age but may persist for a few more years.

The usual presenting symptoms include upper respiratory tract infections (in about 66% of patients), lower respiratory tract infections (in approximately 50% of patients), allergic manifestations (in 50% of patients) and gastrointestinal difficulties (in 10% of patients.) Typically children have a combination of these symptoms. For infants with recurrent or persistent infections, common sense measures such as reducing exposure to infections and prompt and appropriate treatment of respiratory infections are warranted. Live viral vaccines (measles, mumps, rubella, Varicella, Rotavirus) should be postponed. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is not usually necessary except in rare instances when infections are severe and the child is not thriving. Most children with THI develop age-appropriate levels of IgG by age 3; 40% by age 5, with 10% persisting with THI beyond this age.

+–

WHIM Syndrome (Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections, and Myelokathexis)

WHIM Syndrome is a rare congenital immune deficiency, characterized by Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia (a reduction in infection-fighting antibodies), Infections, and Myelokathexis (a disorder of the white blood cells that causes severe, chronic leukopenia and neutropenia) – that form the acronym of its name. Individuals with WHIM syndrome are more susceptible to potentially life-threatening bacterial infections. To a lesser degree, they are also predisposed to viral infections, particularly human papillomavirus (HPV) which can cause skin and genital warts and can potentially lead to cancer.

Generally, symptoms first appear in childhood, with repeated bacterial infections, commonly, middle ear infections, skin infections including cellulitis, impetigo, folliculitis, and abcess, bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, painful infections of the joints, dental cavities, and infection of the gums. Therapy may include immunoglobulin replacement therapy, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to bolster production and maturation of neutrophils and reduce the incidence of infection. Prompt and aggressive treatment of infection is necessary. Vaccinations against HPV should also be considered. Because of the small number of identified cases, the lack of large clinical studies, and the possibility of other genes influencing the disease outcome, we do not have an accurate picture of prognosis.

+–

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS) is unique among PI diseases because, in addition to being susceptible to infections, patients have problems with abnormal bleeding. For patients with WAS this leads to unique health challenges. In its classical form, it has three main clinical features: an increased tendency to bleed caused by a significantly reduced number of platelets, recurrent bacterial, viral and fungal infections, and eczema of the skin. In addition, WAS patients also have an increased risk of developing severe autoimmune disease and have an increased incidence of cancer, particularly lymphoma or leukemia.

Affecting boys, WAS is caused by mutations in the WAS gene. Mothers or sisters, who carry one copy of the disease gene, do not develop symptoms. Because patients with WAS have abnormal T- and B-lymphocyte function, they should not receive live virus vaccines, which may cause them to contract the disease being vaccinated against. WAS patients are treated with immunoglobulin replacement therapy, usually via IVIG to prevent bleeding that may occur with SCIG treatment. Eczema can be severe and persistent, requiring constant care. Autoimmune complications may require treatment with drugs that further suppress the patient’s immune system. Until recently, the only permanent cure for WAS was transplantation of stem cells from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or cord blood. Gene therapy is now showing promise as well. Thirty years ago, WAS was considered fatal, with a life expectancy of only two to three years. Improvements in treatment and other supportive care have improved quality of life and significantly prolonged the survival of WAS patients.

+–

Other Antibody Deficiency Disorders

In addition to the more common immunodeficienies, there are several rare antibody deficiency disorders, including Selective IgM Deficiency, Immodeficiency with Thymoma (Good’s Syndrome), Transcobalamin II Deficiency, WHIM Syndrome, Drug-Indiced Antibody Deficiency, Kappa Chain Deficiency, Heavy Chain Deficiencies, Post-meiotic Segregation (PMS2) Disorder, and Unspecified Hypogammaglobulinemia.

Patients with these Other Antibody Deficiency Disorders usually present with upper respiratory infections or infections of the sinuses or lungs, typically with organisms like streptococcus pneumonia and hemophilus influenzae. The patients often improve with antibiotics but get sick again when these are discontinued. The cornerstone therapy for antibody deficiency disorders is immunoglogulin replacement.

+–

Other Primary Cellular Immunodeficiencies

Other Primary Cellular Immunodeficiencies are characterized by a defect in the T-cell (cellular) immune system, resulting in a different spectrum of infection problems from those individuals with typical antibody deficiency. These include deep-seated bacterial infections, viral and fungal infections, tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections.

Cellular immundeficiencies include Chronic Mucotaneous Candidiasis (CMC), Cartilage Hair Hypoplasia (CHH), X-linked Lymphoproliferative (XLP) Syndromes 1 and 2, X-linked Immune Dysregulation with Polyendocrinopathy (IPEX) Syndrome, Veno-occlusive Disease (VODI), Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson Syndrome (Dyskeratosus Congenita), Immodeficiency with Centromeric Instability and Facial Anomalies (ICF), Schimke Syndrome, and Comel-Netherton Syndrome. All are usually more difficult to treat and may need cellular reconstruction via hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or eventually perhaps gene therapy.

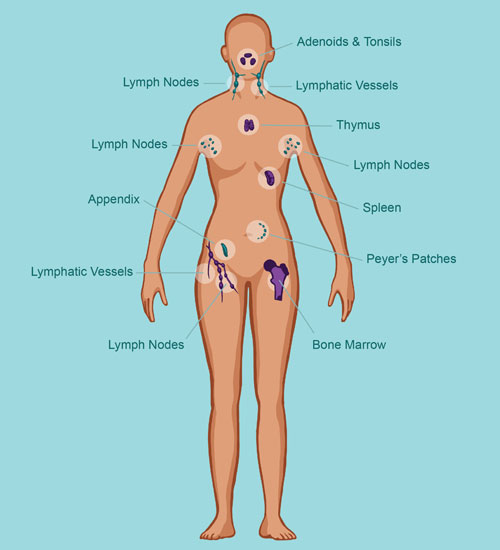

Organs of the Immune System

Organs of the Immune System